Argos Multilingual Welcomes Jan Bareš as Chief Technology Officer

Blog

・16 min read

Software errors found after release can cost up to five times as much to fix as those uncovered during the design stage. Incorporating localization from the beginning can lower your company’s costs – and your developers’ blood pressure!

It’s easy for localization to be overlooked when a software development team is in the product design phase. Development teams are busy with gathering user requirements, developing components, and testing usability in the source language (probably English) – until the moment when the product manager says, “This is great! Let’s sell it in 15 countries!”

However, if localizability hasn’t been built into the product, developers can be thrown into a costly, time-consuming spiral of retrofitting global needs onto a product, delaying global release cycles and creating ugly provisional workarounds that add unnecessary complications to both native and international release processes. What seemed like a great idea – to amortize development costs faster through global expansion – can rapidly become the source of sleepless nights for both the product manager and the development team.

The goal of software development for the global marketplace should be to create a “world-ready” application. This process is often referred to as internationalization, and it makes sure that software can be run anywhere and in any language. This means the application should be able to support any regional time and date or numbering formats and should be ready to be translated into any language, even bi-directional languages or those using different scripts and alphabets.

The key to localizability is designing software and resources that don’t require re-engineering or code modification after the translation process. The first step on the road to a “world-ready” application is achieving the clear separation of user interface (UI) resources from functionality-related resources. The best way to do this is by using file formats that suit localization teams, which enables both the use of professional translation tools and potential automation, which becomes a key element when developing and localizing in Agile environments. The next step is measuring the success of any localizability efforts, and the easiest way to do that is by running localizability testing tasks.

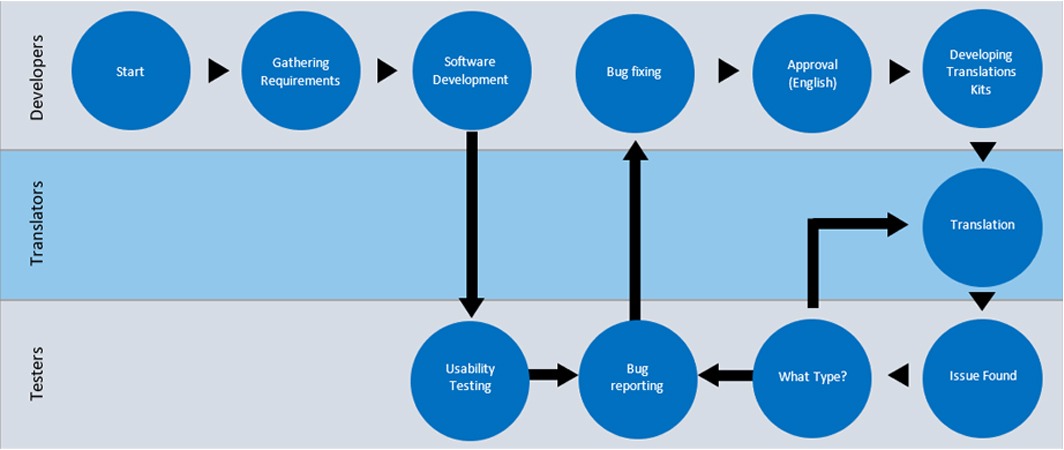

There are typically three interdependent functional teams involved in launching a global product: developers, translators, and testers. As the process flow diagram illustrates, usability testing takes place prior to the launch of software in its original language as well as after translation. Localization testing can result in two types of issues:

It might seem obvious, but the key to a successfully localized software product is allowing linguists to do the best job possible. Even the best linguists need to have a solid understanding of the original product if they are to produce a great translation, and reducing the number of functionality issues relating to world-readiness is one factor that will allow linguists to get the translation right first time.

When it comes to giving linguists what they need to do the job correctly, context is the single biggest factor. In software localization, context is king. Provide as much contextual information as possible, and your product will reap the benefits. The perfect scenario is a full visualization of the UI during translation, but other elements can also be very helpful:

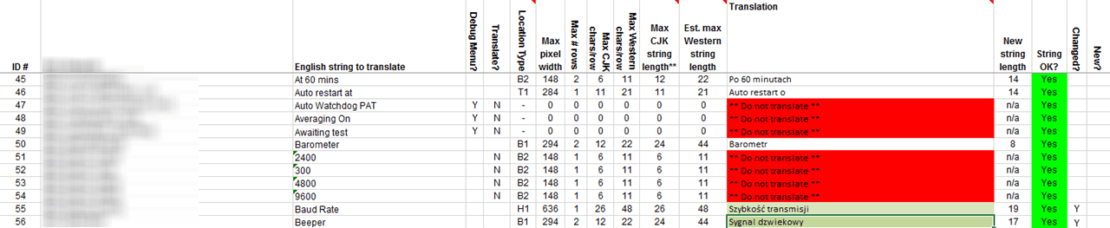

In examples where localizability has not been built into the development process and where the product manager decides that the product should be sold globally, a developer is often quickly reassigned to produce “translatable” resources. In practice, these developers are very often tempted by easy looking formats like Excel files, where linguists are expected to insert translations into their language’s column parallel to the English string.

Once translation is completed, a developer then needs to copy and paste translations back into the code. It should not surprise anyone to learn that hurried copy and paste operations in an unfamiliar language are rarely done right the first time!

The following is an example of such a translatable file in Excel format:

As you can see, the developer put a great deal of effort into creating the file and has included useful information, such as where the string is found and maximum string lengths. Although the file might look cumbersome, the developer has done a decent job in this example – it is significantly better than many localization files received as recently as 10 years ago. However, these formats are not easy to process in a translation workflow, and it is important to get developers and localization engineers talking together at the same table to hammer out the available options. In most situations, there are better ways to handle the UI files. Today’s linguistic technologies are far more advanced, and a little forethought can result in a much smoother localization process.

Where should you start? Usually, the best place to begin is the software development framework being used. Most modern software development frameworks provide tools to extract UI content from code and guidelines on how to create code that can be easily processed for localization. These tools produce files in formats supported by translation tools like .resx, .properties, .po, and .ts files.

Processing UI content with translation tools gives linguists access to many advanced features, such as translation memory, terminology databases, and automated quality checks right at the translator’s fingertips as part of the translation environment. These features help speed up the production of high-quality translations.

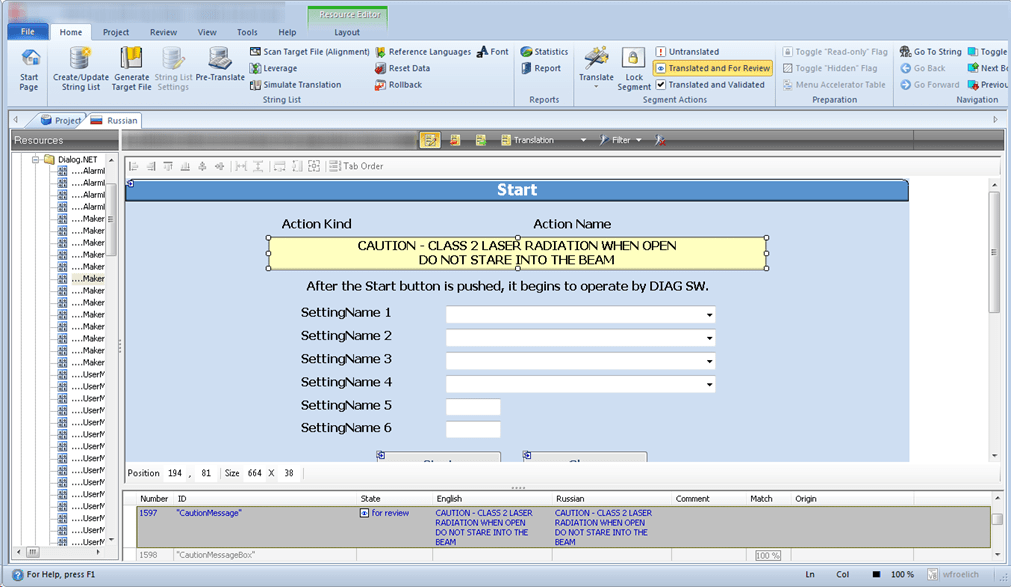

Some frameworks even enable linguists to preview UI while translating. This is usually the best possible scenario – translators see the translation immediately in the right context, they see what type of element is being translated, and they can also see the potential space limitations.

Unified formats for UI translation are a key element in the automation of hand-off/hand-back processes in Agile workflows. Without automation, Agile localization processes cannot integrate with Agile development processes, and there is no automation if formats are not clearly defined.

The following is a preview generated from a .resx Windows Form by a popular translation tool. As you can see, there is plenty of useful information for linguists, including the string ID, development comments as well as a preview of the dialog, which will help linguists understand how a dialog is used and whether there are any string length limitations.

Custom XML files can also be previewed, and because XML files can be easily processed for translation, additional info such as comments about usage or context can also be included for linguists, giving them the best possible chance of getting translations right the first time.

The major problem with incorporating localization late in the development process is that it complicates the process of resolving language-related issues that are discovered during or after translation and during localization testing. These issues are likely to require some development re-work and are likely to happen at a very critical moment in the timeline – right before the release. A study by the Systems Science Institute at IBM found that the cost of fixing an error found after product release was four to five times as much as one uncovered during design.

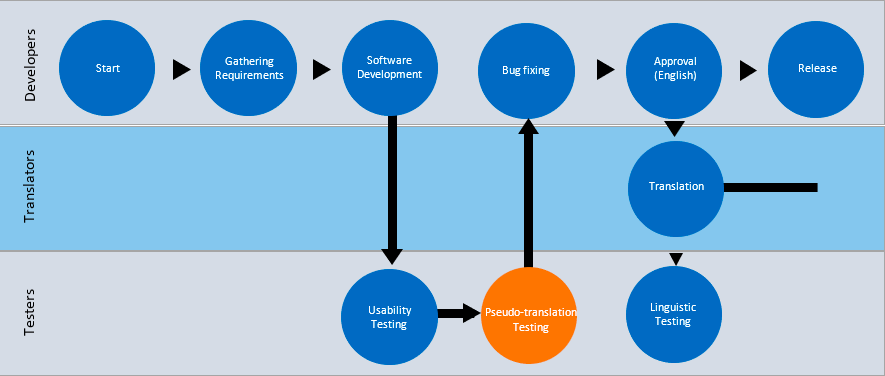

For localized products, these costs have the potential to be multiplied by the number of target languages. If localizability testing is not carried out before English approval, each testing team for each target language will spend time discovering and reporting the same issues. They will then each need to run regression testing on the same bugs. This can be avoided if localizability testing is brought forward in the product development cycle. If we modify the earlier process a little (by running localizability testing in sync with usability testing) we can avoid these issues altogether. The revised process flow below shows a pseudo-translation testing phase in orange.

This means that developers will exchange localizable files with the translation team even before source content is approved. Introducing pseudo-translation testing helps to identify language-related issues early in the process, so there is still enough time to go back to developers and fix any language-related issues. Once the source content is approved, it can be translated and linguistically tested, safe in the knowledge that the number of issues requiring developer intervention has been minimized because they were discovered and fixed much earlier in the process.

At its most basic, pseudo-localization refers to a very rapid and cost-effective method of mimicking the effects of the translation process – without the costs and scheduling impact of a real translation. Pseudo-localization simulates the translation of all resource strings, and usually involves the following:

All these changes can be automated, so all UI resources can be modified using similar patterns that make issues easy to identify in newly built resources. Pseudo-translated resources can be used to rebuild an application and test it. The way it functions should be the same as the original version. Thanks to the patterns used while pseudo-translating resources, it is easy to detect the following issues:

Just as complex projects should be followed by a post-project review, it is also worth closing the development loop by creating and maintaining code development guidelines that include localization-related guidelines. These guidelines should reflect the results of code audits and localization process issues that were fixed in the past. For projects with large volumes of code, there are third-party tools that can automate the code review process.

Localization providers are typically happy to participate in this process, as it helps them to perform great work the first time around in the future. In conclusion, world-readiness is perfectly compatible with the development process as long as you take steps to bring your localization partners onboard early on, perform pseudo-translations to test localizability before translations begin, and use a format that allows linguists to do their jobs.

Contact us to learn more about how we help our clients keep up with the demands of a global marketplace.

What to read next...

Want to know more?

The latest industry news, interviews, technologies, and resources.

View all resourcesGet in touch

We are committed to giving you freedom of choice while providing subject matter expertise and customized strategies to fit your business needs.

Contact us